In an increasingly digital world, the very definition of “physical media” is being challenged, nowhere more pointedly than in the hallowed halls of Japan`s National Diet Library. A recent decision by one of the world`s largest archives has sparked a crucial conversation about the longevity of video games and the complexities of preserving digital culture for future generations.

The Custodians of Culture Take a Stand

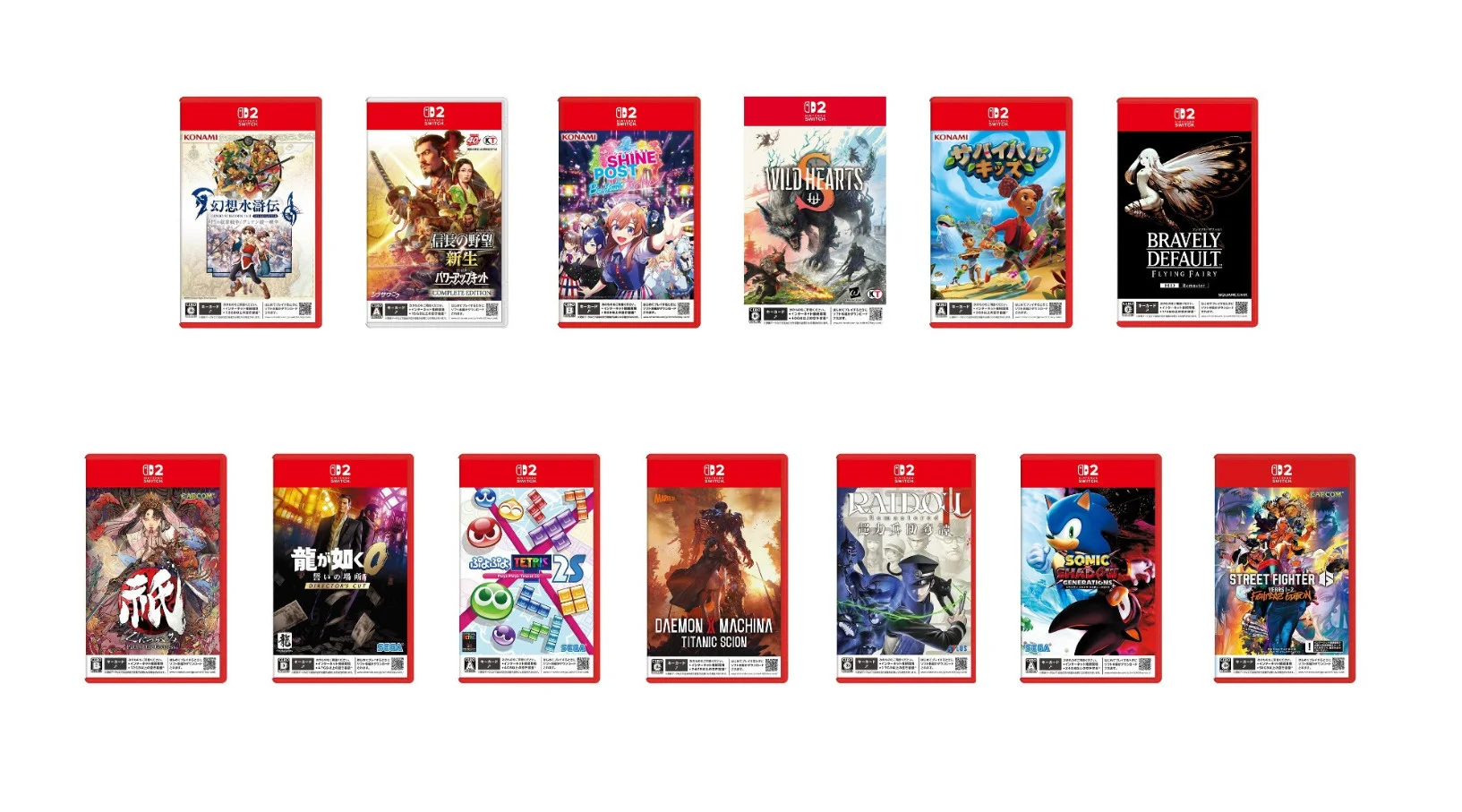

Japan`s National Diet Library (NDL), a venerable institution often likened to the U.S. Library of Congress, has a comprehensive collection of over 44 million items. Among these are more than 9,600 video games, meticulously collected since October 2000, ensuring a tangible record of gaming history. However, the NDL recently declared that it will not accept Nintendo Switch 2 Game-Key Cards into its extensive archives. The reasoning is both technical and deeply philosophical: the game data, it turns out, isn`t actually on the card.

“A key card, on its own, does not qualify as content,” representatives from the NDL explained to Famitsu, highlighting that the data itself resides elsewhere. This technicality places these cards firmly outside the library`s scope for collection and preservation, which traditionally focuses on self-contained physical media.

The Illusion of the Physical: What is a Game-Key Card?

For those uninitiated into the nuances of modern gaming distribution, a Game-Key Card for the Nintendo Switch 2 (and indeed, some previous iterations) is less a game cartridge and more a sophisticated voucher. When inserted into the console, it acts solely as an authentication key, triggering the download of the full game onto the system`s internal storage or an external memory card. The card, in an ironic twist, must remain in the system to play the downloaded game, even though it contains no executable code itself.

This format, utilized by several third-party publishers including Capcom (who classify these as digital sales), presents a perplexing paradox. You hold a physical object in your hand, pay for it in a physical store, but your “ownership” is fundamentally tied to a digital infrastructure. It`s akin to buying an empty book cover with a QR code inside that lets you download the actual novel—and then requires the cover to be physically present every time you want to read it. A rather elaborate form of DRM, if you ask some.

The Specter of Digital Obsolescence: Why This Matters

The NDL`s decision isn`t just bureaucratic nitpicking; it`s a stark reminder of a looming crisis in digital preservation. Consumers, preservationists, and even developers have voiced significant concerns about the format`s implications for game longevity and true ownership. The primary anxiety stems from the inherent reliance on a stable internet connection and the continued functionality of publisher-controlled digital storefronts and servers.

The recent closure of the Wii U and 3DS eShops in March 2023 serves as a grim cautionary tale. Once those digital doors slammed shut, it became impossible to legitimately purchase or redownload many titles from those platforms through official channels. Games tied exclusively to those digital ecosystems, or those that used similar “key card” mechanisms, effectively vanished from official circulation. In a world where a physical key card simply points to a server, what happens when that server goes dark?

Nintendo`s Survey: A Glimmer of Awareness?

Perhaps recognizing these growing concerns, Nintendo recently conducted a survey among its customers, probing their preferences for physical games. While the results are yet to be fully analyzed, the very act of asking suggests an industry grappling with the desires of its consumer base versus the economic efficiencies of digital distribution. Could this indicate a potential shift, or merely an attempt to gauge the depth of player attachment to tangible game cartridges?

The Broader Implications for Digital Archives

This incident transcends just Nintendo or video games. It underscores a fundamental challenge for all archiving institutions in the digital age. How do you preserve “content” when it exists in a fluid, network-dependent state rather than on a self-contained medium? The NDL does collect digital materials like e-books and magazines, but pointedly, it does not include online-only video games. This distinction highlights the unique complexities that interactive software presents, especially when its existence is tethered to external services.

As our cultural output becomes increasingly digital and ephemeral, the definition of what constitutes a “record” or “artifact” must evolve. Libraries and archives, traditionally bastions of physical knowledge, are now navigating a treacherous new landscape where “ownership” is often a license, and “preservation” means grappling with server uptime, proprietary formats, and corporate policies. The decision by Japan`s National Diet Library is not an indictment of innovation, but a solemn reminder that while technology advances, the timeless need to safeguard our cultural heritage remains a paramount, and increasingly complicated, endeavor.

Note: This article is an independent analysis based on reported news and aims to explore the broader implications of the topic.